During the second half of the Middle Ages, courtly literature codified love: how to access it as well as how to tell it.

Professor emeritus of medieval literature at the University of Le Mans, Joël Blanchard is a specialist in late medieval literature . He worked extensively on political figures such as Philippe de Commynes and Louis XI and edited a large number of works from this period. In Poétiques de l’amour , he departs from his favorite fields to evoke courtly literature, its relationship to love and to women. With mixed success.

The book essentially deals with courtly literature and its avatars. The expression “courtly love”, invented by Gaston Paris in 1883 , did not exist in the Middle Ages, which preferred the expression ” fin’amor ” (“pure love” in Occitan). This poetic form, which appeared around the 11th and 12th centuries , celebrates the love between a servant knight and his noble lady, according to very specific codes which reproduce the social order and the hierarchy between lord and vassal.

Of course, this new poetic form does not arise suddenly: it draws its roots from ancient traditions. The texts of Saint Paul and the fathers of the Church are well known to authors of the Middle Ages and constitute an essential matrix. Augustine’s theory , which advocates marriage as a remedy for concupiscence, notably influences the perception of medieval love.

Trials to “Better”

The development of a discourse on love in the literature of the twelfth century is also due to the rediscovery of ancient texts and to the Gregorian reform , this vast enterprise of reform of the Church which redefines the relations between clerics and laity, but also between men and women.

Among the ancient texts, the sulphurous Art of loving by the Roman poet Ovid occupies a special place. Very often copied in the twelfth century , this manual is full of advice for men and women seeking to seduce, in a more or less honest way: it provides poets of the Middle Ages with a framework of thought. Finally, medical discourse also influences poetic expressions of love: doctors sometimes associate courtly love with illness, because it involves suffering . Too much love, not enough love, all contribute to the imbalance of moods and can cause illness.

These theological and medical discourses are coupled with the social organization of the second half of the Middle Ages to model courtly love. Most of the themes of courtesy are already present in the ten poems attributed to Guillaume, Duke of Aquitaine , at the end of the 11th and the beginning of the 12th century.

The themes of love from afar, absence and prohibitions are at the heart of this literature which creates new standards for expressing love.

Like William, troubadours who sing of courtly love were often aristocrats who express chivalrous love. The lady’s love is won by warlike exploits. The applicant must submit to tests imposed by the lady, in particular the assag (the “trial” in Occitan), a night at her side during which the knight-poet must not “act beyond measure” , in other words don’t have sex with her.

These tests aim at the melhorar (“becoming better”) of the courteous lover, that is to say at his moral improvement: ” Courteous is the passion which draws from the obstacle the means of making it an ethic, a finer joy, an ecstasy.” The courteous knight must show moderation and patience and resist the “lauzengiers” , slanderous men. The themes of love from afar, the absence of the lady, or even prohibitions are also at the heart of this abundant literature, which creates new standards for expressing love.

These tests aim at the melhorar (“becoming better”) of the courteous lover, that is to say at his moral improvement: ” Courteous is the passion which draws from the obstacle the means of making it an ethic, a finer joy, an ecstasy.” The courteous knight must show moderation and patience and resist the “lauzengiers” , slanderous men. The themes of love from afar, the absence of the lady, or even prohibitions are also at the heart of this abundant literature, which creates new standards for expressing love.

A misogynistic literature?

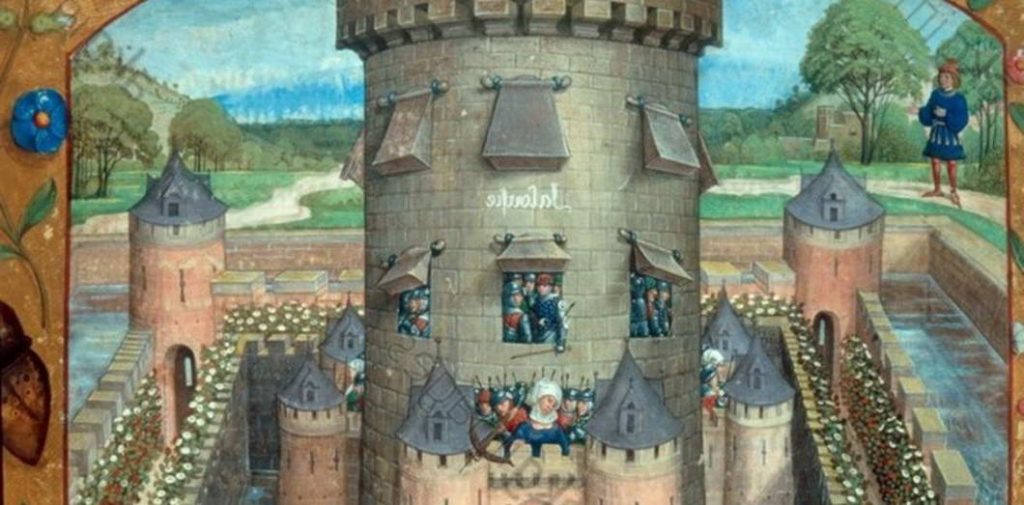

The servant knight therefore derives his legitimacy from the love of his lady, but also from his position as a writer: in the 14th century , Guillaume de Machaut brought together amorous vassalage, submission to the lady, and service linked to writing . This aristocratic position linked to love was reinforced at the end of the Middle Ages, for example with the creation, on February 14, 1401, of the Court of Love , an association of poet lords who sought to celebrate women and cultivate poetry . The court, organized on the model of the princely courts of the time, has up to 952 members!

Courtly literature also gives rise to controversies, such as that of the Roman de la Rose . Le Roman is a singular work, composed in two stages, first by Guillaume de Lorris in the 1230s, then taken up more than thirty years after his death by Jean de Meun . It is the story of a dream, during which the author-narrator is in a wonderful garden populated by allegories and personifications such as Love, Reason, Jealousy, or the Old Woman and Friend. In the part composed by Jean de Meun, the longest, the tone changes: Jean de Meun is inspired by the doctrines of Aristotle and The Art of Loving. Over 300 manuscripts of the work survive, with additions or cuts.

The Roman de la Rose arouses many debates and controversies. Some, like Philippe de Mézières, argue that the Roman de la Rose is unfair to women. From 1401, a debate agitated the literary spheres: Jean de Montreuil defended the genius of Jean de Meun, while he opposed in particular the famous Christine de Pizan and Jean Gerson.

The latter castigate the Roman and in particular his cynical vision of love. Christine de Pizan advises, for example, to read Dante’s Divine Comedy instead of the Novel and Ovid, which she despises. The Roman de la Rose is therefore “read and understood as a writing directed against women.

Moreover, it is not the only openly misogynistic writing of the Middle Ages : other texts depict love relationships between men and women as disastrous. The fabliaux are sorts of tales which regularly have as their subject conjugal life and sexuality : the woman there is often unfaithful, deceitful and insatiable.

In this vein, Mathéolus , a lawyer who married a widow, writes Lamentations about his unhappy marriage and the dramatic consequences for him: he considers himself a martyr to marriage. These misogynistic discourses are superimposed on those of courtly love and give a complementary vision of the way in which the medievals considered love literature.

Gender Anachronisms

The ambitious subtitle of Poetics of Love is Sexuality, Gender, Power , but it is hard to understand why. Admittedly, the history of the genre is fashionable and we can only rejoice in it. However, it is not enough to proclaim that one studies gender to truly adopt a gendered approach. It is in this that Poétiques de l’amour is disappointing and constitutes, in reality, a synthesis of the poetic discourse of the second half of the Middle Ages and not a work dealing with gender and sexuality.

One cannot consider the XII E century as a “century of freedoms in all kinds”, only because the poets sing the love for the lady.

The introduction already shows all the limits that must be brought to this beautiful subtitle: the genre is only superficially defined. The other concepts are not further developed. The reader will not know what love was exactly in the Middle Ages. The history of emotions and feelings, however, invites us to put the uses of these notions into context: love is above all a social construct and responds to different standards depending on the period.

In addition, Joël Blanchard slides quite lightly from love to friendship or sexuality, but without establishing the boundaries between these notions even though in the Middle Ages, sexuality was not really correlated with love in the Nowadays sense. We cannot therefore consider the twelfth century as a “century of freedom of all kinds” , only because the poets sing of love for the lady.

Even more problematic is the place of women in the work. Gender studies invite researchers not to make anachronisms and not to overestimate or underestimate the place of women in history. Using the terms “feminism” or “anti-feminism” , as the author does, does not really make sense: the Middle Ages are certainly misogynistic, but they do not know the notions of female emancipation and do not conceptualize not the type according to these grids.

Talking about free women about Héloïse writing to Abelard or the character of the bourgeoise of Bath in the eponymous tale by Geoffrey Chaucer is also an anachronistic reading. She certainly starts from a good feeling, that of qualifying the misogyny intrinsic to medieval society, but she ignores the impossibility for women to free themselves from a male referent, except perhaps in widowhood and in very specific circumstances. particular.

Where are the medieval authors?

Finally, the gender approach implies constantly confronting the place of men and that of women, not isolating the latter. In this sense, the very structure of the book shows a certain incomprehension of the concept: two out of fourteen chapters are devoted to women authors.

The first is only ten pages long, the second deals almost exclusively with Christine de Pizan, whose work Joël Blanchard knows well. We would have liked to be able to compare more clearly the word of the poetesses with that of the troubadours and go beyond Christine de Pizan: the insistence on exceptional women hides the cohort of other medieval women authors .

In short, Poétiques de l’amour does not meet the objectives of its subtitle and it is all the more unfortunate that the publisher (Passés Composites) seeks to show the dynamism of historical thought , in particular to the attention of the general public. The dynamism of gender studies deserved better. Poétiques de l’amour is nevertheless a pleasant read and is full of examples which, if we do not speak of genre, illustrate the dynamism of medieval literature itself.